Tonya Nelson

Can 3D imaging technologies be used to create accurate digital ‘replicas’ of museum objects? The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at University College London (UCL) collaborated with UCL’s Civil, Environmental, and Geomatic Engineering (CEGE) Department and Arius3D Inc, commercial producer of 3D scanners, to answer this question. 3D imaging technology is not new and is actively used across many academic disciplines and professional practices, such as medicine, architecture, and manufacturing. However, none of these disciplines require the same level of accuracy of colour, texture and form needed for collections-based academic research and practice in the heritage sector. The Petrie Museum was selected to be a partner in this research because its diverse collection of small objects from ancient Egypt – ivory combs, limestone jars, blue frit scarab beetles, and linen-based foot covers – was considered ideal for testing the capability of 3D technologies to capture subtle variations in hue, surface texture and shape found in heritage objects. The Petrie Museum staff was also considered important to the endeavour – it was its curators and conservators who would ultimately be the judge of the fidelity of 3D digital replicas, so it was important that they were integrated into the R&D process from the start.

As it turns out, the answer to this question is not a simple yes or no. An assessment of ‘accuracy’ is highly dependent on context. Is a 3D image accurate for the purposes of creating an online digital exhibition for the general public enjoy? Yes. Is that same image accurate enough for a researcher to understand whether the object comes from the same manufacturing site as similar objects in different museums? Maybe not. Such comparisons would require the inspection of minute texture and colour details that the technology was struggling to capture accurately. Not to mention that colour on screen is highly dependent on the calibration of the individual monitor. However, the accuracy of 3D images produced from laser scanners in terms of shape is very high and for some research inquiries, comparing 3D digital replicas would be more efficient and accurate than hand measuring the physical objects.

These insights raised a series of new research questions that expanded the project and depth of collaboration between the Petrie, CEGE Department and Arius3D. How can we use 3D images to advance public engagement with collections? How can they be used to advance scientific research of heritage collections? How do we embed the production and use of 3D technology into heritage organisations?

Advancing Public Engagement Using 3D Images

Visiting museums can be a passive experience. There will always be a barrier between the viewer and the object that impedes engagement with collections. The question then becomes whether 3D digital images can act as surrogates, providing opportunities for virtual interaction and engagement. As part of the UCL collaboration, a software developer was hired to work with Petrie Museum staff to pilot a range of web and mobile applications for visitors that would help answer this question.

The first web-based application developed was Crossing Over, which is an interactive online exhibition articulating how the ancient Egyptians prepared for the afterlife. A series of 3D digital images of objects appear on the screen as the user reads small sections of text about each. When the user advances to the next section, the object automatically rotates on the screen to focus on the particular area of the object the text is referencing. The user may also zoom in and zoom out to see fine details that would never be possible in a typical museum setting. Within the Museum, Crossing Over was shown on a 3D monitor so that visitors could view the objects in stereo 3D (like a 3D movie). The application has proven particularly successful with children and young people who see it as something similar to a video game. In a study conducted about the use of digital interactives in the Museum, the Petrie team found that Crossing Over increased enthusiasm to see the objects use in the application and promoted deeper engagement with the objects.

The Petrie also saw the opportunity to use 3D images to help give more context about where objects were found. In the study of ancient Egypt, archaeologists and researchers heavily rely on the grouping of objects in tombs to understand their use and function. However, rarely do we see ancient Egyptian artefacts displayed in their tomb groups. In order to aid this type of presentation, the Petrie Museum developed mobile application called Tour of the Nile. The objective of the application was to allow users to ‘discover’ where objects were excavated along the Nile. In order to do this, the Petrie produced a large scale floor map with digital markers in places where artefacts were found. Using a mobile device, the user could walk the Nile and see 3D images of objects on their device as they approached different archaeological dig sites. The user receives information about the dig site as well as the opportunity to learn more about the objects found there. This was seen as the first step in a more ambitious project to create an immersive virtual reality installation that would allow the visitor to step into the world of the archaeologist and see the tomb and objects in situ in stereo 3D.

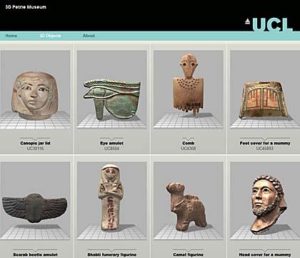

In addition to using 3D to give objects more geographical context, the Petrie developed a the 3D Petrie website aimed at providing temporal context for the object so that users could understand each object’s: (1) function in ancient Egypt; (2) site of excavation and archaeological history; and (3) housing and care in the Petrie Museum and any recent research related to it. Small details that provide evidence and clues about an object’s history are identified and users are invited to manoeuvre the 3D image to examine features in ways not possible with 2D photographs or through visual inspection of the object on display in the Museum.

The Petrie Museum undertook an evaluation of the impact of digital interactives (both 2D and 3D) on public engagement and learning. A mixture of tools were used to assess audience impact – focus groups, learning tests, and observation. Overall, the study found that digital engagement using 3D images increased interest in the collection. For children and young people, the web and mobile applications mirrored the type of games and applications they routinely engage with and enjoy and so made the museum experience more relevant. Generally, younger audiences felt more enthusiastic about seeing the physical object once they had engaged with it digitally. On the other hand, older audiences were more interested in seeing the physical object first but found benefit in being able to see objects in more detail through 3D images afterwards. However, while it is clear that 3D interactive add engagement, it is not clear that they aid in learning or information retention. An experiment that tested the knowledge acquisition of two groups – one that was provided information via 3D applications and one that was provided the same information through label and print material – saw no difference in learning.

Advancing Collections-Based Research and Teaching

The 3D Petrie website also provides a prototype image library linked to its catalogue. The Petrie collection is a highly sought after international resource because it is one of the few Egyptian collections that is documented. The Museum holds the journals and archaeological records of Flinders Petrie, who excavated the large majority of objects in the collection. While the Petrie was one of the first museums in the UK to provide online access to its entire collection with 2D images, there is still great demand for research visits to the Museum. High quality 3D images provide greater opportunities for remote object assessment and thus is a route to serving the research community more efficiently. The next stage of the website development will link 3D images to digitised records, journals and notes that will allow full access to the Petrie’s resources and provide a mechanism for crowd-sourced interpretation and analysis of associated documents.

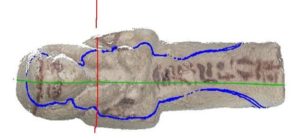

It is clear having 3D interactive images of objects is better than 2D static images, but does the technology offer new research methods? Despite real questions about the ability of 3D scanning technology to render colour and texture accurately, it is clear it can capture size and shape with high accuracy. The UCL CEGE Department calculated that the Arius3D scanner could produce single point accuracy of the order of 25 microns in terms of dimension. The diameter of a human hair is 75 microns. How could this level of accuracy be used to advance research? The Petrie Museum holds thousands of shabtis, many of which look almost identical. A number of archaeology researchers have asked whether these shabtis were produced from the same mould or from the same production site. While physical measurement of the shabtis would provide some evidence to answer this question, one of the members of the 3D research team discovered a simpler, more accurate and less invasive manner of addressing the question. He layered a series 3D images of shabtis on top of each other on screen and rotated the images in different directions in order to ascertain where they aligned. He was also able to use an online measuring tool to record the exact dimensions of each shabti across several different points. Using this methodology, he was able to identify shabtis that were likely produced from the same mould.

Discussions with archaeology teaching staff revealed a much more basic use for the 3D image library: object analysis. One of the first skills budding archaeologists develop is the ability to examine objects and make assessments about age, composition and use by closely inspecting the colour, texture, and shape. Teaching staff at UCL reported that students were not given enough opportunities to sharpen their assessment skills and remote access to the 3D images of archaeological material could help students prepare for exams. Taking the 3D image library one step further, the Petrie developed a web-based application that provided a platform for students to create exhibition catalogues. Students select objects from the image library, assess the object by rotating the 3D image and prepare catalogue entries providing measurements and descriptions of the object that indicate the age, type and use of the object. The application then generates a catalogue that can be printed or submitted electronically to their instructor for grading. The application was piloted in a first year archaeology course and the course instructor reported that the scored for the object assessment element of the final exam improved as a result of students having more practice through the Petrie Museum 3D cataloguing tool.

Embedding 3D Imaging Processes into Heritage Organisations

The collaborators on the UCL 3D research project thought it was important that the process of creating a 3D images was critically examined. If heritage organisations are to embrace 3D technology as a means of improving access and engagement with their collections, the implications for embedding the process of imaging in day to day business needed to be addressed.

The 3D research team included a curator and conservator from the Petrie Museum who helped establish a workflow that could be adopted by most museums. The founding principle of the workflow was that an object should only be imaged once – ‘one and done’ – in order to avoid unnecessary handling and damage. Hence, the highest quality image should be produced in the first instance, even if this level of quality is not needed for immediate use. When selecting objects for imaging, the curator and conservator assessed the qualities of the objects that made it a good candidate for laser scanning (as opposed to other types of 3D image capture technology, such as photogrammetry or RFD). Objects with a high gloss, for example, are better suited to photogrammetry than laser scanning because of issues of light reflection. Once selected, the team would create an object record that would document the technology used, date of image creation, scanner data and the curators’ assessment of the quality and accuracy of the final 3D image. The record would note, for example, if any post-production colour correction was necessary to reflect the true appearance of the object. Or if no correction could be made, the record would identify for the viewer where there were deviations from the original object. These records would then be appended to the image library along with information from the catalogue entry for the physical object. A more extensive discussion of the workflow process can be found here.

The essential element of embedding 3D imaging practice into a museum or heritage organisation is upskilling existing staff. Producing a high volume of 3D images takes time and is unsuitable for project staffing. However, the skills required for a 3D imaging programme are not dramatically different from skills that already exist among museum staff. In the Petrie, a conservator was trained to be the imaging technician. Museum conservators routinely photograph objects for condition assessments and reports and so are skilled in taking technical pictures with appropriate detail. The conservator was trained to use the Arius3D laser scanner fairly easily. The critical task is to ensure the laser passes over the entire surface of the object by repositioning and rotating the object on the scanner bed and reviewing all the scanned images on the attached monitor. A curator was assigned to the project assess the quality of the 3D images produced, determine what type of metadata should be included with the image and develop exhibitions and digital applications using them. A dedicated software developer was hired onto the Petrie Museum staff in order to develop prototype web and mobile applications using the 3D images. While it may not be possible for a small and medium size museums to employ a software developer on a permanent basis, it is recommended that someone employed on a project basis work alongside the permanent team so that they understand the needs of the organisation, create applications that can be easily updated and amended, and share their expertise with the staff.

Conclusion

The museums and heritage sector could benefit in a number of ways from 3D imaging programmes. This article has outlined how research at UCL evolved from asking the question about where it was possible to create high quality 3D images of museum objects to how 3D images could be used to advance public engagement, research and teaching. This article has not explored the ways in which 3D reproduction could be used to boost museums economically, but there is greater potential there. The key to a successful 3D imaging programme is embedding it into the organisation. Hence, it requires the time and attention of senior management to ensure the benefits for the organisation are known to all staff and they have the opportunity to participate in the process.

For more information about UCL’s work in the area of 3D imaging in museums, please see the publication list here.

Tonya Nelson

Head of Museums and Collections at University College London

ist die Leiterin der Museen und Sammlungen des University College London (UCL). In den letzten fünf Jahren lag ihr Fokus in der Sammlungsstrategie darauf, die Sammlungen zugänglicher und das Internet und mobile digitale Technologien nutzbar zu machen. Sie arbeitete mit den Instituten der Informatik, des Ingenieurswesens sowie den Digital Humanities des UCL. Sie setzte sich für die Produktion von hochqualitativen 3D Reproduktionen von Kulturerbe ein, sodass die Veröffentlichung einer interaktiven 3D Datenbank auf der Webseite mit Objekten aus dem Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology des UCL möglich wurde.