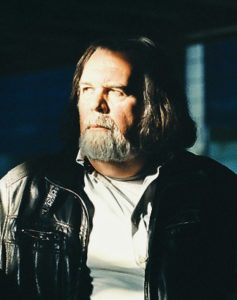

Peter van Mensch

There is a diffuse distinction between Museum Studies, Museumswissenschaften, Museumswissenschaft, Museumsphilosophie, Museumskunde, Museology, and Museography. Throughout the present paper, I deliberately use the term Museology. In a variety of contexts the term Museology refers to museum practice (such as in Latin-America), sometimes specifically exhibiting, sometimes documentation and/or conservation. Also in Germany, the term Museologe refers to a practitioner, usually in the field of documentation, even though since the early 20th century the term Museumskunde has been used to denote museum practice. In Germany, the term Museologie has an ambivalent status. It was first used by Georg Rathgeber, director of the Herzogliche Gemälde-Gallerie zu Gotha in 1839 (DESVALLÉES/MAIRESSE 2005, p. 131). It refers to the curatorial practice of arranging works of art in exhibitions, in storage, and in catalogues. The term was again used in 1869 by Philipp Leopold Martin in a handbook on natural history museums (MARTIN 1869). Martin defined Museology as “das Aufstellen und Erhalten von Naturaliensammlungen”. In 1878, Johann Georg Theodor Graesse started the journal Zeitschrift für Museologie und Antiquitätenkunde sowie verwandte Wissenschaften in which he in 1883 described Museology as “Fachwissenschaft” (GRAESSE 1883). In the course of the twentieth century, the term Museology was increasingly used for the theory of museum practice, usually in connection with academic training programmes (LORENTE 2012). In Germany the body of knowledge and experience concerning museum practice itself was referred to as Museumskunde. In France the term Muséographie was being used for this. Following the French practice, Museology and Museography were being adopted by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) at the proposal of its (French) director, George Henri Rivière in 1958. Museology was defined as “la science ayant pour but d’étudier la mission et l’organisation du musée”, and Museography as “l’ensemble des techniques en relation avec la muséologie” (DESVALLÉES/MAIRESSE 2005, p. 134) . Under the influence of English speaking members, the term Museography gradually disappeared from the ICOM rhetoric. Museology as the theory of and reflection on museum work was embodied in the ICOM International Committee for Museology (ICOFOM), founded in 1977. In its understanding of Museology as (academic) discipline, ICOFOM followed a Central-European tradition. In socialist countries, Museology as (academic) discipline was well established (LORENTE 2012).

In Great Britain and the United States the term Museology never became popular, partly because the discipline was (in general) not being recognized as academic. At universities, Museum Studies was mostly being used as equivalent of Museumskunde (LORENTE 2012, p. 240). However, after the publication of Peter Vergo’s anthology The New Museology (1989), New Museology became widely accepted as genuine academic field of interest (with no reference to the Central-European tradition). Vergo defines museology very much in line with common practice around the world as “the study of museums, their history and underlying philosophy, the various ways in which they have, in the course of time, been established and developed, their avowed or unspoken aims and policies, their educative or political or social rôle” (VERGO 1989, p. 1). He continues to say that Museology “might appear at first sight a subject so specialised as to concern only museum professionals […] but […] it is a field of enquiry so broad as to be a matter of concern to almost everybody”. According to Vergo, “Old Museology” is too much about museum methods, “New Museology” focusses on “a radical re-examination of the rôle of museums within society” (VERGO 1989, p. 3). Vergo’s book not just illustrates this shift of focus, but is also an expression of an emerging interest of academic researchers outside the museum field. As New Museology gradually became part of a broader Cultural Studies discourse, there currently is a tendency to replace the term New Museology by Museum Studies. In German translation this obviously became Museumswissenschaften (plural).

The four volume International Handbooks of Museum Studies (2015) is firmly rooted in the New Museology discourse of the 1990s and early 21st century. The use of the terms (New) Museology versus Museum Studies is not consistent. In their introduction to the first volume (on Museum Theory), the editors, Kylie Message and Andrea Witcomb, use both terms more or less interchangeable with a slight preference, it seems, for museum studies. However, they do not consider museum studies as analogous to nor subsumable under cultural studies. They regret that New Museology/Museum Studies “have been criticized for becoming ‘too theoretical’ and abstracted from the empirical world at hand”, but “the intention articulated by many contemporary museum studies researchers to overcome distinctions between different spheres of action (theoretical and professional) […] may make a contribution to cultural studies’ aim to cross disciplinary boundaries” (MESSAGE/WITCOMB 2015, p. xliii-xliv). At the other side, although Museum Studies “has the unique advantage of a focused site of analysis”, the contribution to museum practice is less clear. Since their perspective on museology does not reach back beyond the publication of The New Museology, they do not seem to be aware of the existence of a long “Werdegang” of what has been set aside as Old Museology.

Friedrich Waidacher’s Handbuch der Allgemeinen Museologie (1993) and Katharina Flügel‘s Einführung in die Museologie (2005, third edition in 2014) are very much defined by the continental European (mainly Central-European) tradition. Their main source of inspiration is the Czech/Czechoslovakian museologist Zbyněk Stránský (1926-2016). Waidacher does not refer to Vergo’s The New Museology. Neither does Flügel who completely neglect the British developments of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In her Museumswissenschaften (2006), Hildegard Vieregg develops a more international perspective than Waidacher and Flügel, but she too fails to recognise the importance of the New Museology discourse. The title of her book is not a German version of Museum Studies, but refers to four fields of study: Museumsgeschichte, Museologie, Museumspädagogik, and Museumsdidaktik, suggesting that each field of study is a Wissenschaft in its own right (VIEREGG 2006, p. 9) . Her concept of Museology is less elaborated upon than in Waidacher’s and Flügel’s publications. The most recent handbook in German language is Markus Walz’ Handbuch Museum (2016). In his own contributions, Walz shows that he is familiar with the international discourses but he also shows his debt to the Central-European tradition (Stránský).

Zbyněk Stránský was one of the most influential theoreticians in Central-European museology (VAN MENSCH 2016a, p. 370). He also played an important role during the early years of ICOFOM. Outside ICOFOM his work has hardly been published in English, so in the English speaking museological (or, rather museum studies) world he thus remained largely unknown. Apart from the Czech and Slovak Republics, the most fertile soil for Stránský’s ideas was and is Germany. Difference should be made between the former German Democratic Republic and the Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Among museologists of the German Democratic Republic, Stránský was well known and well respected. Before 1989, he was not very well received in the Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Mainly thanks to Friedrich Waidacher (Graz) and Christian Müller-Straten (München), Stránský’s ideas became recently known to a wider German speaking audience (VAN MENSCH 2016b).

In general, museologists all over the world were attracted to Stránský because he elaborated a consistent system of museology built around some discipline-specific concepts, such as musealisation and museality. Such a system was helpful in developing consistent study programmes. To Stránský developing a consistent system was crucial in his lifelong endeavour to prove that museology is a genuine academic discipline, but this concern was of little interest in “western” countries. Apart from obvious personal ambitions, the aim to have museology recognized as academic discipline and to claim a position of the discipline within the academic framework was shared with all former socialist countries and had to do with the special importance given to museums as ideological instruments. It also had to do with the concept of professionalism. Much earlier than in Western Europe it was understood that museum work requires specialised training in addition to knowledge in the relevant subject matter field(s). This specialised training should be based on a consistent theoretical understanding of the museum phenomenon. For example, the DDR handbook for history museums Museologie. Theoretische Grundlagen und Methodik der Arbeit in den Geschichtsmuseen (1988) starts with an elaborate chapter on “Museologie als wissenschaftliche Disziplin” (written by the Russian museologist Avraam Razgon). In the chapter on “Forschung im sozialistischen Geschichtsmuseum” distinction is made between “Geschichtswissenschaftliche Forschung” and “Museologische Forschung”. Not history (as a science) should be the basis of history museums, but museology. “Alle Museen sollten deshalb auch museologische Forschungsstätten […] sein” (HERBST/LEVYKIN 1988, p. 75).

In the mid-1970s, Dutch museum authorities felt the need to redefine professionalism. There was an urgent need for specialists in the fields of registration/documentation, collections management, conservation, exhibiting, education, and marketing. “New professionals” entered the museum field. They did not necessarily have competencies related to the subject matter field of the museum, but there was a general feeling that they should have a basic understanding of the specificity of museum work. To provide for such knowledge, a specialised training programme was established in 1976: the Reinwardt Academie (Leiden, since 1992 Amsterdam). Although students were introduced to collection related subject matter fields (art history, history, anthropology, natural history), they were not trained as curators, this being considered to be the exclusive domain of university training programmes. As compared to other training programmes the Academie created a unique situation with museology as binding rationale behind the curriculum instead of a collection related subject matter discipline. Museology was seen as genuine discipline (with its own lecturer), not as an applied science. There were few studies programmes that could offer some guidance. Actually, there were initially two programmes that served as source for inspiration: the Museum Studies Programme at the University of Leicester (founded in 1966), and the Fachschule für Museumsassistenten (founded in 1954 at Köthen, DDR; since 1966 Leipzig). The professional perspective of the Leipzig programme came closer to the approach of the Academie (both being a higher vocational programme preparing for non-curatorial positions in museums) than that of the Leicester programme (an academic programme focussing on curatorial positions).

Seen from the perspective of Leiden/Amsterdam there were many similarities between the approaches as developed at Leicester and those applied in Leipzig, albeit the term Museology was hardly used in Leicester. At Leicester, Susan Pearce focussed on objects and collections. By doing so, she developed a vision on the rationale behind museum work in a similar direction as expressed in afore mentioned DDR handbook for history museums. At the Reinwardt Academie we could easily identify with these approaches. It helped us to define the specificity of museum work and to connect the different disciplines that are applied in museums. For example it helped us to develop a curriculum that created a common basis for educators and conservators, for registrars and exhibition designers, etc. It also helped us to address new challenges, such as the musealisation of “new heritage”. Key terms were value, significance, or – in Stránský’s words – museality (VAN MENSCH 2015). In more recent years, the different approaches that were applied in the Reinwardt curriculum merged into the methodology developed by the Australian Heritage Collections Council. Under the title Significance it published a method for valuing collections (VAN MENSCH 2016a, p. 372). The model defines significance as “the meanings and values of an item or collection through research and analysis, and by assessment against a standard set of criteria” (RUSSELL/WINKWORTH 2001, p. 10).

In the meantime, Central-European museology stagnated in its development. In Leicester New Museology took root. Richard Sandell was one of the key persons working on the concept of social inclusion. This principle became the cornerstone of the concept of the Socially Purposeful Museum as proposed by the Leicester School of Museum Studies in 2012. The Socially Purposeful Museum is “a dynamic, vital institution that has rich relationships with diverse audiences; that nurtures participatory and co-creative practice and is part of people’s everyday lives; that seeks to foster progressive social values and, at the same time, is widely recognised as a site for dialogue and debate; that works collaboratively with a range of institutions within and beyond the cultural sector to engender vibrant, inclusive and more just societies” (DODD 2015). This thinking is rapidly developing into a dominant rhetoric in the international museum field, especially in the international committees of ICOM with a strong British participation. Unfortunately, there has never been a strong participation in the activities of ICOFOM by museum workers and museum researchers from Great Britain, United States, Australia and New Zealand. Instead there is a strong participation from Latin-American countries. As a result there appears to be a growing gap between “the” Museology as advocated by ICOFOM, and the New Museology/Museum Studies discourse. It would be interesting to make a comparative study of the curricula (and reading lists) of German museology/museum studies programmes to see to what extend they identify with one of the two “schools of thought”. Or perhaps one of the three “schools of thought”, because to complete this brief overview, it is necessary to pay attention to the emergence of Heritage Studies as alternative for Museology/Museum Studies.

In 1981, the philosopher Hermann Lübbe gave a lecture at the Institute of Germanic Studies (University of London) (LÜBBE 1981). This lecture made the concept of musealisation popular in the German speaking world (ZACHARIAS 1990). Lübbe appears to be well informed about the discourse in the English speaking museum world, but is not aware of the fact that Stránský did introduce the concept already more than a decade before (VAN MENSCH 2016b). A few years after Lübbe’s lecture David Lowenthal published his book The past is a foreign country (LOWENTHAL 1985). Lowenthal refers to a variety of German authors, but not to Lübbe (nor Stránský or other authors from socialist Europe). Although he does not use the concept of musealisation, there are many similarities between Lowenthal and Lübbe. Lübbe’s ideas were recently proposed as basis for a new field of study: Museumphilosophie. Lowenthal became the intellectual father of an other new field of study: Heritage Studies.

The contents of the International Journal of Heritage Studies (since May 1994) give a good impression of the roots of the discipline and how it developed around the turn of the century. Like the term heritage itself, Heritage Studies initially consisted of a mixture of archaeology and historic preservation (care for monuments and sites), with landscape and landscape preservation as overarching concepts. However, from the very beginning museums were being addressed. Parallel to the developing New Museology discourse – and obviously inspired by it – Heritage Studies became increasingly the study of heritage as cultural and social process, about how “the idea of heritage is used to construct, reconstruct and negotiate a range of identities and social and cultural values and meanings in the present” (SMITH 2006, p. 3). The International Journal of Heritage Studies became a major advocate of this critical, cross-disciplinary approach which Rodney Harrison coined as Critical Heritage Studies (HARRISON 2013). Just as Peter Vergo’s New Museology, Harrison’s Critical Heritage Studies became a movement, culminating in the foundation of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies in 2012. One of the aims of the Association is to increase dialogue and debate between researchers, practitioners and communities. Within this framework it seeks to integrate heritage and museum studies with studies of memory, public history, community, tourism, planning and development.

In a world in which the boundaries between museums and other heritage initiatives are increasingly blurring, an integral and integrating perspective is of paramount importance (HEUMANN GURIAN 2005; VAN MENSCH /MEIJER-VAN MENSCH 2015, Chapter 5). The community at large might not be interested in how we professionals – practitioners and researchers – compartmentalize our fields of interest. It would be worthwhile to explore the benefits of re-defining Museum Studies programmes as (Critical) Heritage Studies programmes. But, one important question needs to be answered: do we still perceive museums as heritage institutions?

References:

DESVALLÉES, André/MAIRESSE, François 2005: Sur la muséologie. In: Culture & Musées 6. Jg., S. 131-155.

DODD, Jocelyn 2015: The socially purposeful museum. Museologica Brunensia 4. Jg., H. 2, S. 28-32.

FLÜGEL, Katharina 2005: Einführung in die Museologie. Darmstadt.

GRAESSE, Johann Georg Theodor 1883: Die Museologie als Fachwissenschaft. In: Zeitschrift für Museologie und Antiquitätenkunde sowie verwandte Wissenschaften 15. Jg., S. 113-115.

HARRISON, Rodney 2013: Heritage. Critical approaches. London.

HERBST, Wolfgang/LEVYKIN, K.G. (Hrsg.) 1988: Museologie. Theoretische Grundlagen und Methodik der Arbeit in Geschichtsmuseen. Berlin.

HEUMANN GURIAN, Elaine 2005: A blurring of the boundaries. In: CORSANE, Gerard (Hrsg.): Heritage, museums and galleries. An introductory reader. London, S. 71-77.

LORENTE, Jesús-Pedro 2012: The development of museum studies in universities: from technical training to critical museology. In: Museum Management and Curatorship 27. Jg., H. 3, S. 237-252.

LOWENTHAL, David 1985: The past is a foreign country. Cambridge.

LÜBBE, Hermann 1981: Der Fortschritt und das Museum. Über den Grund unseres Vergnügens an historischen Gegenständen. The 1981 Bithell Memorial Lecture. London.

MARTIN, Philipp Leopold 1869: Praxis der Naturgeschichte. Weimar.

MENSCH, Peter van 2015: Museality at breakfast. The concept of museality in contemporary museological discourse. In: Museologica Brunensia 4. Jg., H. 2, S. 14-19.

MENSCH, Peter van 2016a: Museologie – Wissenschaft für Museen. In: WALZ, Markus (Hrsg.): Handbuch Museum. Geschichte – Aufgaben – Perspektiven. Stuttgart, S. 370-375.

MENSCH, Peter van 2016b: Metamuseological challenges in the work of Zbyněk Stránský. In: Museologica Brunensia 5. Jg., H.2 (in print).

MENSCH, Peter van/MEIJER-VAN MENSCH, Léontine 2015: New trends in museology. Celje.

MESSAGE, Kylie/WITCOMB, Andrea 2015: Introduction: Museum theory. An expanded field. In: MESSAGE, Kylie/WITCOMB, Andrea (Hrsg.): Museum theory. The International Handbooks of Museum Studies 1. Chichester, S. xxxv-lxviii.

RUSSELL, Roslyn/WINKWORTH, Kylie 2001: Significance. A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections. Canberra.

SMITH, Laurajane 2006: Uses of heritage. London.

VERGO, Peter (Hrsg.) 1989: The new museology. London.

VIEREGG, Hildegard Katharina 2006: Museumswissenschaften. Eine Einführung. Paderborn.

WAIDACHER, Friedrich 1993: Handbuch der Allgemeinen Museologie. Wien.

WALZ, Markus 2016: Handbuch Museum. Geschichte – Aufgaben – Perspektiven. Stuttgart.

ZACHARIAS, Wolfgang 1990: Zeitphänomen Musealisierung. Das Verschwinden der Gegenwart und die Konstruktion der Erinnerung. Essen.

Professor Dr. Peter van Mensch

Freier Museologe, Berlin

ist freier Museologe und Museumsberater und lebt in Berlin. Vorher war er als Professor für Kulturelles Erbe an der Reinwardt Academy, Amsterdam University of the Arts (Niederlande) und als Professor für Museologie an der Universität von Vilnius (Litauen) tätig. Aktuell unterrichtet er als Gastprofessor an der Universität Bergamo (Italien). International war und ist er unter anderem beim International Council of Museums (ICOM) aktiv. Er arbeitete in den internationalen Komitees Education and Cultural Action (CECA), Museology (ICOFOM) und Collecting (COMCOL), und ist nun im Komitee für Museumsethik aktiv.