Dr. Kevin Moore

This paper explores three inter-related themes, on the role of the curator, the role of the curator in exhibitions, and the role of research in exhibitions, as follows:

- Let’s talk about ….Curators

How are the responsibilities of curators changing? Is there a new professional image for curators?

- Curators and Exhibitions

What can we expect from exhibitions in the future? What is the social and academic relevance of exhibitions? What is the future role of curators in exhibitions?

- Research and Exhibitions

Do exhibition theories help exhibition practice? What is the role of subject specialist academics in exhibition research?

- Let’s talk about ….Curators

Let’s talk about curators! I have been working in the museum sector in the UK since 1985, but for only two years of that time has my job title been ‘curator’. As discussed below, the term is decreasingly being used in UK museums. I was a Lecturer in the Department of Museums Studies, University of Leicester, the world’s leading centre for postgraduate teaching and research in Museum Studies, between 1992 and 1997. In that time I taught over six hundred existing and future curators from around the world. I have been the Director of the National Football Museum for England since 1997. I have therefore taught, worked with and met a very large number of ‘curators’ (whatever their actual job title may have been) over the past thirty years. They have been increasingly female, overwhelmingly white and middle class in background. While museums in the UK have increasingly sought to attract and serve the most diverse and inclusive audiences, their workforce has not and does not reflect society as a whole. How can museums fully understand and engage with society if their curatorial workforce does not reflect it?

Who was the first curator? In Ancient Rome, ‘curators’ were senior civil servants in charge of various departments of public works. In the Medieval period a ‘curatus’ was a priest devoted to the care (or ‘cura’) of souls. Aren’t we still doing this in some way? The special objects aren’t buried with us in our graves any more, they go into museums, where through them we can live on, and achieve immortality. This is after all why wealthy individuals donate millions to museums for new galleries in their name. There is a spiritual dimension to museums as repositories and public spaces. The National Football Museum has been described many times by the public and the media as the ‘spiritual home of the game’, a place ‘where the players and fans of the past come alive at night’. We have on loan for display the ashes of a great English footballer of the 1940s and 1950s.

If you put the word ‘curator’ into a well-known search engine’s image search you get largely images of young women. This reflects how the profession has changed in the last thirty years or so, from male to female, at least at junior levels. If you put the phrase ‘old curator’ into the same search engine, you get largely images of older men with beards. If you use the German word ‘Kustos’, we get the same images of women curators as for ‘curator’ in English. In the past curators were largely male and white and did not reflect society as a whole. However, this does not mean we should dismiss the work that they did. Indeed, there should be more histories of curators and curatorship.

Until very recently the public had a rather negative perception of curators, who were to a large extent seen as old white men with beards, almost like Father Christmas. Except unlike Santa Claus, they do not give gifts, but take gifts for the museum’s collection from the public, every day of the year: curators are the antithesis of Santa. Curators were and still are

to an extent perceived as genial, but slightly eccentric, if not actually mad, sat alone in a dusty museum surrounded by ancient bones and stuffed animals, especially rather creepy birds. Though I don’t have beard, I am a middle aged white man, and therefore fit the public perception of a curator. People ask me what I do all day at work. I ask them what they think I do. They presume I sit, rather bored, surrounded by old footballs and football shirts, waiting for members of the public to donate objects or ask me to identify their object and give them a valuation. To some extent the public have confused the roles of curators with antique dealers. When I say that I am the director of the museum, many people are puzzled. They refer to me instead as the curator or the head curator. They often have no concept that a museum needs leadership or even management. In calling me a ’curator’ rather than a ‘director’ the public are actually correct, in terms of the dictionary definition of curator in English, which is both ‘the administrative head of a museum, art gallery, or similar institution’, and ‘someone who is in charge of the objects or works of art in a museum or art gallery’, ‘14th century, from the Latin: one who cares, from curare, to care for, from cūra, care’. In any case, their lack of understanding is not their fault, it’s ours! We need to communicate much more clearly to the public what it is we actually do, beyond the public spaces and exhibitions of the museum. We need to explain why we exist and what we do, what the different roles are in the museum, including curators. How many museums even clearly display their mission statement to the public in the museum itself or on its website?

Things are changing, and indeed we now have almost a cult of the curator, especially in art galleries, and in particular those of contemporary art. Major exhibitions are ‘curated’ by named curators. There is a trend that sometimes the gallery’s curators are not up to the task and that a (usually well known) artist instead needs to be brought in to curate the exhibition. We now have books such as On Curating: Interviews with Ten International Curators (Thea, 2009), and an Artspace article informs us of ‘8 Super-Curators You Need to Know, From Massimiliano to HUO’. We now have to an extent the curator as a kind of ‘auteur’, an Alfred Hitchcock figure. Curating is now cool and has spread from the museum to other areas of culture. Rock festivals, film festivals and food festivals are now curated. One could say that the conference from which this paper is derived was curated. Curating has become commercial. I have seen a row of designer shops in a street off Carnaby Street in London that have been ‘curated’. I fully expect soon that in an international chain coffee shop my latte will be curated for me.

We can see how the image of the curator has changed if we look at representations of curators in popular culture, such as films. Curators were portrayed as nerds, such as Cary Grant (who amazingly manages to look and act like a nerd) in the 1938 hit comedy film Bringing up Baby, with Katherine Hepburn. By 2015 curators in films are much cooler and indeed sexier but also potentially rather evil, such as Nicole Kidman in the film Paddington.

Yet in museums if not in art galleries in recent years we seem to have lost faith in curatorship and the term curator. To some extent we have the death of the curator, as museums in the UK and elsewhere increasingly do not use the term, seeing it as old fashioned, and instead increasingly using job titles such as collections manager. But this isn’t just a renaming of the role of the curator, but also an increased division of the responsibilities. The job in larger museums is increasingly divided into roles such as registrar, collections manager, exhibitions manager, public programming etc. Only in smaller museums, where there are only one or two professional staff, where this person or persons have to do everything, does the term still get widely used. I’m not sure that this division and specialisation of the elements of the role of curator is helpful. We have divided the role, but then when, for example, we have a major new exhibition project, we need to bring back together these subdivision specialists. Maybe we have specialized too far. Maybe we just needed a team of curators who can actually do all these tasks: collections acquisition, collections management, research, exhibitions development, audience engagement and public programming. The word ‘curator’ is now a powerful one. We should be proud of it, embrace it again, modernise its image, reclaim it and use its power.

- Curators and Exhibitions

What can we expect from exhibitions in the future? Who are exhibitions for? What is the social and academic relevance of exhibitions? Simplifying, in the beginning curators made exhibitions for curators. They engaged in detailed, lengthy research, and produced exhibitions that were effectively a book on the wall, with elements of taxonomy in all subject matters, not just natural history. Often in the past curators were effectively failed academics, people who wanted to be a university lecturer but didn’t make it, and so museums were the next best placed to continue their personal research interests. This to an extent still exists in museums today. Twice recently I have heard in a presentation by a curator that ‘I have been working on this exhibition for 20 years’. To which the answer should be ‘Do it now. Or give up, there is a reason it hasn’t happened, no one but you wants it and no one is prepared to back it!’

The pressure in the 1980s in the UK for museums to attract greater audiences and to generate income from exhibitions led to a rejection of the curator-led exhibition. Instead, designers were given all the power in exhibitions. In some cases, even in national museums, the curators were cut out altogether, beyond some fact-checking. However, designers were not making the exhibitions for the public, but for themselves, to test out new approaches and technologies, to impress other designers … and to win design awards! The exhibitions were usually stylish but often vacuous in content. Increased pressure for museums to generate income then led to the marketing and commercial departments being given control of exhibitions, leading to ‘blockbusters’ to bring in the most visitors, to make the most money. These were successful to an extent, but to a degree this led to dumbed down content, and controversial subject matters being ignored.

Clearly exhibitions are not for curators, designers or marketeers, they are for the audience. All exhibition teams need a balance of skills and input from, among others: curators; designers; marketing; commercial; learning staff; and audience advocates, including those who specialise in access issues for people with a range of disabilities. A major exhibition is like a movie, with sometimes hundreds of contributors. Exhibitions are a highly collaborative process involving a great deal of teamwork. Unlike a film they succeed not just from one person’s vision and instead need and greatly benefit from the creative involvement of a large number of people, with a variety of skills. Exhibitions do not succeed by having a Hitchcock-like ‘auteur’ figure.

- Research and Exhibitions

Do great exhibitions results from:

- An academically informed approach?

- An audience informed approach?

- Or simply from a great subject matter?

An academically informed archaeology gallery tends to look like a book on the wall with objects as illustrations of a quasi-academic narrative, description and analysis.

An audience informed archaeology gallery looks like Jorvik Viking Centre, York, UK, which is a multi-sensory journey back to Viking York at 5:30 pm on 25 October 975 AD. Museums purists hated Jorvik when it opened in 1984 – and some still do – saying it is more like a theme park ride than a museum exhibition. But the public loved it then and still do today, and over 20 million people have visited. It’s based upon very thorough research of the highest standards. So in this sense it cannot be faulted. But the exhibition created is also highly effectively informed by the needs and desires of its audience.

A great subject matter is usually a winner, but it’s not just the popularity of the subject matter which means that the National Football Museum for England attracts over 500,000 visitors each year in Manchester. A football museum can fail to attract an audience if its exhibition approach is ill-considered. A number of major football club museums have closed, failing to attract the anticipated audiences. The National Football Museum succeeds because of its audience centred exhibition approach. The potential audiences were consulted at length

throughout the exhibition process. However, great subject matter displayed much less well can still be a success with the public. To take three examples from the UK, which are not museums but which are to an extent perceived as such by the public. ‘The Chocolate Story’ in York and ‘Cadbury World’ in Birmingham (also about chocolate) are highly successful in

audience terms if not in my view as exhibitions – but the subject matter overrides this. A great subject matter even done really badly can still be a hit with the public. ‘The Beatles Story’ in Liverpool is in my view a rather poor exhibition, little more than an open display of a private collection of not particularly impressive memorabilia. But because there is no other major display of Beatles memorabilia in the city, not even at the Museum of Liverpool, it is highly popular. As I wrote in my book Museums and Popular Culture in 1997, if public museums do not engage with popular culture, ‘they will be bypassed by a private museum sector, with no public accountability or necessarily any attempt at objectivity’ (Moore, 1997: 94).

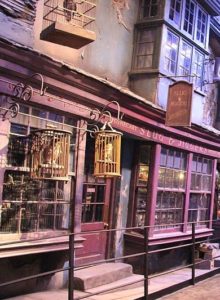

In the UK at least this has to a large extent happened, with commercial attractions such the ‘British Music Experience’ in London (moving to and reopening in Liverpool in 2017). Notably, for the new version of this attraction in Liverpool this is now also termed ‘the UK’s Museum of Popular Music’. ‘The Warner Bros. Studio Tour London: The Making of Harry Potter’ is an outstanding museum in all but name, as it is based on the real sets, props, costumes and other artefacts from the series of Harry Potter films, which were made at the site of the attraction. Some museums have engaged much more closely with popular culture,

such as the Museum of Liverpool, and the opening of the National Football Museum in 2001 marked the creation of a museum of a key aspect of England’s popular culture. The V and A has held an increasing number of blockbuster temporary exhibitions on popular culture, such as on Kylie Minogue, David Bowie and 1960s popular music and its political impact, ‘You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970’, for which some commentators have accused it of dumbing down. Has the V and A fully embraced popular culture or seen such exhibitions simply as potentially very effective income generators? The V and A has not created a permanent display of popular culture. My call that museums need to fully embrace popular culture is as relevant now as it was at the time of writing in 1997.

How far are exhibitions informed by academic research on exhibitions? Into the 1990s there were a relatively small number of academic publications on exhibitions. There are now a large and rapidly growing number. Museum staff simply don’t have time to read all this. But Museum Studies courses, because of the university environments they are in, at least in the UK, have become more academic and much less practical. There is little applied research, the academic research and publishing has little impact on museum practice, including exhibitions. Museum staff learn about exhibitions to an extent from professional publications, websites and organisations, but in my view these in turn are largely not drawing upon the academic research and publications. Museum staff largely learn about exhibitions from other exhibitions. But maybe this is better anyway. Exhibitions are the applied research. If they work, copy and learn from them! Yet there clearly is value in the academic research and writing on museum exhibitions. The academics need to communicate their research much more effectively with museum staff if it is to have any significant impact.

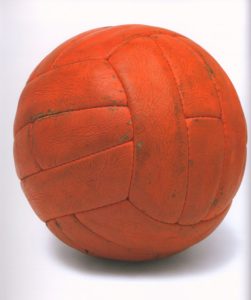

What of the relationship between exhibitions and subject matter academic research? Exhibition is a unique form of communication. Apart from art historians, many academics, such as historians, are largely not interested in material culture, mainly still only drawing upon written and printed sources. Yet material culture is at the heart of museums and exhibitions. To show what was possible to historians a chapter of my book Museums and Popular Culture was an object study of the ball from the 1966 FIFA World Cup Final (Moore, 1997: 106-134), and similarly I have published an academic paper on Diego Maradona’s shirt from the Argentina versus England FIFA World Cup quarter final match in 1986 (Hughson and Moore, 2012). Museums need to encourage subject specialist academics to study our material collections, not just our archives, to inform our exhibitions (for a discussion of this, see Moore, 2013).

Conclusion

The future of curating will definitely be as much female as male, but it must also be as much female as male at the level of museum directors. Future curators must also reflect society in terms of not just gender, but also social class, ethnicity and sexuality. The role of the curator is splitting as more skills in museum work are required, beyond collections management and research. Wider public engagement requires new skills, such as marketing, audience development, and learning and community engagement. It’s impossible for one person to have all these skills! Though of course in the smallest museums, with only one or two professional staff, these curators have to somehow have all these skills. Successful exhibitions now require a much greater range of skills than those traditionally held by curators, but this does not mean the death of the curator. Indeed, I think we need to reclaim the term, which is powerful, and stop using terms that mean nothing to the public, such as collections manager, registrar, or exhibitions manager. The new curators need to widen the subject matter of museums to include popular culture to a much greater extent, learning from visitor attractions. In this they can be assisted and guided by museums studies academics and subject specialist academics, but these need to find a way to much more closely engage with and communicate with museum staff. The traditional curator is dead, but long live the new curator! Carry on curating!

References

Hughson, J., Moore, K., 2012, ‘ “Hand of God”, Shirt of the Man: The Materiality of Diego Maradona’, Costume. The Journal of the Costume Society, Volume 46, Number 2 (2012): 212-225.

Moore, K., 1997, Museums and Popular Culture, Leicester University Press, Leicester, UK, 1997.

Moore, K., 2013, ‘Sport history, public history and popular culture: a growing engagement’, Journal of Sport History: Vol. 40, Number 1, Spring: 39-55.

Thea, C.,, 2009, On Curating: Interviews with Ten International Curators, Distributed Art Publishers, New York, USA.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Dr Kevin Moore

Chief Executive at Humber Bridge Board

has been Director of the National Football Museum since the beginning of the project in 1997. He is an experienced museum professional of international stature. He is regularly invited to give papers at museum and academic conferences around the world, and has published a number of major books about museums, including the internationally acclaimed Museums and Popular Culture, Museum Management, Management in Museums and Sport, History and Heritage. Kevin is chair of the Sport in Museums Network, the organisation of the UK’s sports museums, libraries and archives. He is a Visiting Fellow at the University of Central Lancashire, De Montfort University, Manchester Metropolitan University and a Fellow of the RSA.